Fantastic article and SR-71 pilot Brian Shul’s account from the kool page; Breed of Speed!!!!

This is an older story (obviously, since the SR-71 isn’t in official use anymore), but still a good one.

The following passage is from a now out of print book called Sled Driver by Brian Shul (you can still get a used copy on Amazon for around $700 correction $350 here’s a link: http://www.amazon.com/Sled-Driver-Flying-Worlds-Fastest/dp/0929823087).

Here’s the ultimate aviation troll:

There were a lot of things we couldn’t do in an SR-71, but we were the fastest guys on the block and loved reminding our fellow aviators of this fact. People often asked us if, because of this fact, it was fun to fly the jet. Fun would not be the first word I would use to describe flying this plane. Intense, maybe. Even cerebral. But there was one day in our Sled experience when we would have to say that it was pure fun to be the fastest guys out there, at least for a moment.

It occurred when Walt and I were flying our final training sortie. We needed 100 hours in the jet to complete our training and attain Mission Ready status. Somewhere over Colorado we had passed the century mark. We had made the turn in Arizona and the jet was performing flawlessly. My gauges were wired in the front seat and we were starting to feel pretty good about ourselves, not only because we would soon be flying real missions but because we had gained a great deal of confidence in the plane in the past ten months. Ripping across the barren deserts 80,000 feet below us, I could already see the coast of California from the Arizona border. I was, finally, after many humbling months of simulators and study, ahead of the jet.

I was beginning to feel a bit sorry for Walter in the back seat. There he was, with no really good view of the incredible sights before us, tasked with monitoring four different radios. This was good practice for him for when we began flying real missions, when a priority transmission from headquarters could be vital. It had been difficult, too, for me to relinquish control of the radios, as during my entire flying career I had controlled my own transmissions. But it was part of the division of duties in this plane and I had adjusted to it. I still insisted on talking on the radio while we were on the ground, however. Walt was so good at many things, but he couldn’t match my expertise at sounding smooth on the radios, a skill that had been honed sharply with years in fighter squadrons where the slightest radio miscue was grounds for beheading. He understood that and allowed me that luxury.

Just to get a sense of what Walt had to contend with, I pulled the radio toggle switches and monitored the frequencies along with him. The predominant radio chatter was from Los Angeles Center, far below us, controlling daily traffic in their sector. While they had us on their scope (albeit briefly), we were in uncontrolled airspace and normally would not talk to them unless we needed to descend into their airspace.

We listened as the shaky voice of a lone Cessna pilot asked Center for a readout of his ground speed. Center replied: “November Charlie 175, I’m showing you at ninety knots on the ground.”

Now the thing to understand about Center controllers, was that whether they were talking to a rookie pilot in a Cessna, or to Air Force One, they always spoke in the exact same, calm, deep, professional, tone that made one feel important. I referred to it as the ” Houston Center voice.” I have always felt that after years of seeing documentaries on this country’s space program and listening to the calm and distinct voice of the Houston controllers, that all other controllers since then wanted to sound like that, and that they basically did. And it didn’t matter what sector of the country we would be flying in, it always seemed like the same guy was talking. Over the years that tone of voice had become somewhat of a comforting sound to pilots everywhere. Conversely, over the years, pilots always wanted to ensure that, when transmitting, they sounded like Chuck Yeager, or at least like John Wayne. Better to die than sound bad on the radios.

Just moments after the Cessna’s inquiry, a Twin Beech piped up on frequency, in a rather superior tone, asking for his ground speed. “I have you at one hundred and twenty-five knots of ground speed.” Boy, I thought, the Beechcraft really must think he is dazzling his Cessna brethren. Then out of the blue, a navy F-18 pilot out of NAS Lemoore came up on frequency. You knew right away it was a Navy jock because he sounded very cool on the radios. “Center, Dusty 52 ground speed check”. Before Center could reply, I’m thinking to myself, hey, Dusty 52 has a ground speed indicator in that million-dollar cockpit, so why is he asking Center for a readout? Then I got it, ol’ Dusty here is making sure that every bug smasher from Mount Whitney to the Mojave knows what true speed is. He’s the fastest dude in the valley today, and he just wants everyone to know how much fun he is having in his new Hornet. And the reply, always with that same, calm, voice, with more distinct alliteration than emotion: “Dusty 52, Center, we have you at 620 on the ground.”

And I thought to myself, is this a ripe situation, or what? As my hand instinctively reached for the mic button, I had to remind myself that Walt was in control of the radios. Still, I thought, it must be done – in mere seconds we’ll be out of the sector and the opportunity will be lost. That Hornet must die, and die now. I thought about all of our Sim training and how important it was that we developed well as a crew and knew that to jump in on the radios now would destroy the integrity of all that we had worked toward becoming. I was torn.

Somewhere, 13 miles above Arizona, there was a pilot screaming inside his space helmet. Then, I heard it. The click of the mic button from the back seat. That was the very moment that I knew Walter and I had become a crew. Very professionally, and with no emotion, Walter spoke: “Los Angeles Center, Aspen 20, can you give us a ground speed check?” There was no hesitation, and the replay came as if was an everyday request. “Aspen 20, I show you at one thousand eight hundred and forty-two knots, across the ground.”

I think it was the forty-two knots that I liked the best, so accurate and proud was Center to deliver that information without hesitation, and you just knew he was smiling. But the precise point at which I knew that Walt and I were going to be really good friends for a long time was when he keyed the mic once again to say, in his most fighter-pilot-like voice: “Ah, Center, much thanks, we’re showing closer to nineteen hundred on the money.”

For a moment Walter was a god. And we finally heard a little crack in the armor of the Houston Center voice, when L.A.came back with, “Roger that Aspen, Your equipment is probably more accurate than ours. You boys have a good one.”

It all had lasted for just moments, but in that short, memorable sprint across the southwest, the Navy had been flamed, all mortal airplanes on freq were forced to bow before the King of Speed, and more importantly, Walter and I had crossed the threshold of being a crew. A fine day’s work. We never heard another transmission on that frequency all the way to the coast.

For just one day, it truly was fun being the fastest guys out there.

Also found more snippets on FB that we must add. This book must be a phenomenal read!!!!

The SR-71 Blackbird

Interesting information (history)!!

In April 1986, following an attack on American soldiers in a Berlin disco, President Reagan ordered the bombing of Muammar Qaddafi’s terrorist camps in Libya .

My duty was to fly over Libya , and take photographs recording the damage our F-111’s had inflicted.

Qaddafi had established a ‘line of death,’ a territorial marking across the Gulf of Sidra , swearing to shoot down any intruder, that crossed the boundary.

I was piloting the SR-71 spy plane, the world’s fastest jet, accompanied by a Marine Major (Walt),

the aircraft’s reconnaissance systems officer (RSO).

We had crossed into Libya , and were approaching

our final turn over the bleak desert landscape, when

Walt informed me, that he was receiving missile

launch signals.

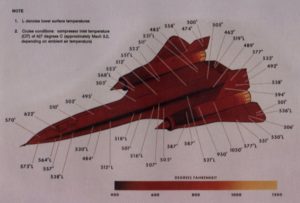

I quickly increased our speed, calculating the time it would take for the weapons, most likely SA-2 and SA-4 surface-to-air missiles, capable of Mach 5 – to reach our altitude.

I estimated, that we could beat the rocket-powered

missiles to the turn, and stayed our course, betting

our lives on the plane’s performance.

On the morning of April 15, I rocketed past the line at 2,125 mph.

After several agonizingly long seconds, we made

the turn and blasted toward the Mediterranean ..

‘You might want to pull it back,’ Walt suggested.

It was then that I noticed I still had the throttles full forward.

The plane was flying a mile every 1.6 seconds, well above our Mach 3.2 limit..

It was the fastest we would ever fly.

I pulled the throttles to idle, just south of Sicily, but we still overran the refueling tanker, awaiting us over Gibraltar …

Scores of significant aircraft have been produced,

in the 100 years of flight, following the achievements

of the Wright brothers, which we celebrate in

December.

Aircraft such as the Boeing 707, the F-86 Sabre Jet, and the P-51 Mustang, are among the important machines that have flown our skies.

But the SR-71, also known as the Blackbird, stands alone as a significant contributor to Cold War victory, and as the fastest plane ever, and only 93 Air Force pilots, ever steered the ‘sled,’ as we called our aircraft.

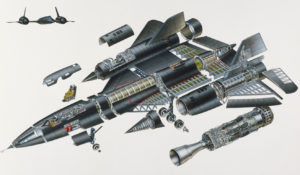

The SR-71, was the brainchild of Kelly Johnson, the famed Lockheed designer, who created the P-38, the F-104 Starfighter, and the U-2.

After the Soviets shot down Gary Powers U-2 in 1960,

Johnson began to develop an aircraft, that would

fly three miles higher, and five times faster, than

the spy plane, and still be capable of photographing

your license plate.

However, flying at 2,000 mph would create intense heat on the aircraft’s skin. Lockheed engineers used a titanium alloy, to construct more than 90 percent of the SR-71, creating special tools, and manufacturing procedures to hand-build each of the 40 planes..

Special heat-resistant fuel, oil, and hydraulic fluids, that would function at 85,000 feet, and higher, also had to be developed.

In 1962, the first Blackbird successfully flew, and in 1966, the same year I graduated from high school,

the Air Force began flying operational SR-71 missions.

I came to the program in 1983, with a sterling record

and a recommendation from my commander,

completing the weeklong interview, and meeting

Walt, my partner for the next four years.

He would ride four feet behind me, working all the cameras, radios, and electronic jamming equipment.

I joked, that if we were ever captured, he was the spy, and I was just the driver.

He told me to keep the pointy end forward.

We trained for a year, flying out of Beale AFB in

California , Karenna Airbase in Okinawa , and RAF

Mildenhall in England .

On a typical training mission, we would take off near Sacramento, refuel over Nevada, accelerate into Montana, obtain a high Mach speed over Colorado , turn right over New Mexico, speed across the Los Angeles Basin, run up the West Coast, turn right at Seattle , then return to Beale.

Total flight time:- Two Hours and Forty Minutes.

The Blackbird always showed us something new, each aircraft possessing its own unique personality.

In time, we realized we were flying a national treasure.

When we taxied out of our revetments for take-off, people took notice.

Traffic congregated near the airfield fences, because everyone wanted to see, and hear the mighty SR-71.

You could not be a part of this program, and not come to love the airplane. Slowly, she revealed her secrets to us, as we earned her trust..

One moonless night, while flying a routine training

mission over the Pacific, I wondered what the sky would look like from 84,000 feet, if the cockpit lighting were dark.

While heading home on a straight course, I slowly turned down all of the lighting, reducing the glare and revealing the night sky.

Within seconds, I turned the lights back up, fearful that the jet would know, and somehow punish me.

But my desire to see the sky, overruled my caution, I dimmed the lighting again. To my amazement, I saw a bright light outside my window.

As my eyes adjusted to the view, I realized that the brilliance was the broad expanse of the Milky Way,now a gleaming stripe across the sky. Where dark spaces in the sky, had usually existed, there were now dense clusters, of sparkling stars.

Shooting Stars, flashed across the canvas every few seconds. It was like a fireworks display with no sound.

I knew I had to get my eyes back on the instruments, and reluctantly, I brought my attention back inside.

To my surprise, with the cockpit lighting still off, I could see every gauge, lit by starlight.

In the plane’s mirrors, I could see the eerie shine of my gold spacesuit, incandescently illuminated, in a

celestial glow.

I stole one last glance out the window.

Despite our speed, we seemed still before the heavens, humbled in the radiance of a much greater power.

For those few moments, I felt a part of something far more significant, than anything we were doing in the plane.

The sharp sound of Walt’s voice on the radio, brought me back to the tasks at hand, as I prepared for our descent.

The SR-71 was an expensive aircraft to operate.

The most significant cost was tanker support, and in 1990, confronted with budget cutbacks, the Air Force retired the SR-71.

The SR-71 served six presidents, protecting America

for a quarter of a century.

Un-be-known to most of the country, the plane flew over North Vietnam , Red China , North Korea , the Middle East, South Africa , Cuba , Nicaragua , Iran , Libya , and the Falkland Islands .

On a weekly basis, the SR-71, kept watch over every Soviet Nuclear Submarine, and Mobile Missile Site,and all of their troop movements.

It was a key factor in winning the Cold War. I am proud to say, I flew about 500 hours in this aircraft.

I knew her well.

She gave way to no plane, proudly dragging her Sonic Boom through enemy backyards, with great impunity.

She defeated every missile, outran every MiG, and always brought us home.

In the first 100 years of manned flight, no aircraft was more remarkable.

The Blackbird had outrun nearly 4,000 missiles, not once taking a scratch from enemy fire.

On her final flight, the Blackbird, destined for the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum , sped from Los Angeles to Washington in 64 Minutes, averaging 2,145 mph, and ,setting four speed records.

[su_button url=”http://wp.me/p2pGLX-1E7″ target=”blank” style=”3d” size=”13″ center=”yes” text_shadow=”0px 0px 0px #000000″ desc=”To see the SR-71 videos!!”]Click here,[/su_button]